Between the eighth and twelfth centuries, a collection of over a thousand stories was prepared in Japan, called the Konjaku Monogatarishū, or Konjaku Monogatari. In English, this translates to Anthology of Tales Old and New. Over thirty-one volumes, the anthology ranges over Buddhism and some regional folklore, but the emphasis is on the former, and the tales are presented like moralistic fairy tales, each one beginning with “In days long ago,” and ending with “and so the story is handed down to us,” along with a moral summary of the tale. The tales come from India, China, and Japan, and are sometimes compared to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, although the stories in Konjaku Monogatarishū are probably closer to the fairy tales collected by the Grimm brothers.

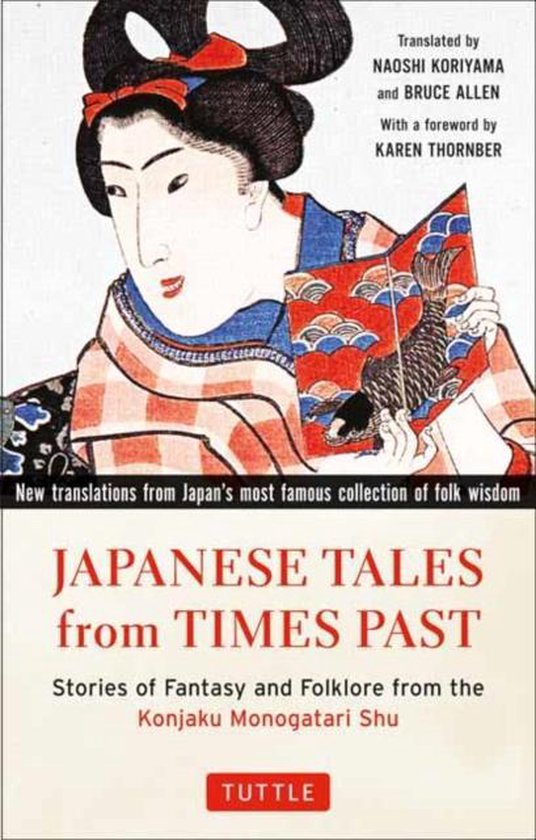

I did not read all thousand-plus stories, but I was intrigued by the collection, and came across a selection of ninety stories from the Japanese parts of the original anthology recently chosen and translated by Naoshi Koriyama and Bruce Allen. Officially titled Japanese Tales from Times Past: Stories of Fantasy and Folklore from the Konjaku Monogatari Shu – New translations from Japan’s most famous collection of folk wisdom, Koriyama and Allen’s translation includes ninety stories and is billed as the largest English collection to be published in a single volume. However, these are not “short stories” as you might be expecting if you’re thinking of modern anthologies and collections like Unfettered, Arcanum Unbounded, or Writers of the Future volumes. Each one reads more like a summary of a short story, told in a straightforward fashion without character internality, amplifying details, or what is colloquially referred to as “showing.” Most of the stories are three pages or less, with a few composed of only a couple of paragraphs – but they don’t feel like so-called flash fiction. That keeps some of them from reading like stories in the sense modern readers understand the word, but as you get into the collection, the approach gives an illusion of sitting and listening to someone telling you a story in the way a friend might tell a story about something they observed. In other words, the storytelling style strongly suggests the oral tradition from which these folktales and religious parables probably arose.

Oddly, the translators do not emphasize the oral heritage which likely formed the basis for the original Konjaku Monogatarishū. Instead, they emphasize the stories’ relevance to modern preoccupations and assumptions, which occasionally informs the translation with anachronistic turns of phrase and presentations which, for me, detract from the experience of the stories and the immersivity of the collection. Nor do their translational choices lead me to the same conclusions and takeaways described in the forward.

While there are similarities in Buddhist monastic traditions to those of Medieval Europe (and I will be reading and reviewing a book specifically examining those eastern monastic traditions in the coming weeks), there is a sense from these stories that they took their monasticism a bit less seriously. That may be the selection of tales, but there is an irreverence that underpins many of the stories, which is not entirely tied to the warning aspect of the tales. Monks pop up with supernatural powers, succumb to worldly temptations, and then reacquire their supernatural powers, like flying around in the air or telekinetically moving logs about, by thinking about it a bit. Many of the stories consist of folksy warnings to read Buddhist texts and follow Buddhist precepts more faithfully, along with ideas of karmic justice. The text frequently refers to this instead as “the law of cause and effect,” which is an insightful framing as it reduces the moralistic component. In the stories, the law of cause and effect is depicted much as it sounds, as a natural and inevitable series of consequences resulting from an action or actions, which is rather different from how “karma” is often imagined in Western circles, as something actively intervening to correct a moral transgression.

Other stories fit firmly into traditional fairy tale molds, moral tales with elements of the supernatural world. Each story ends with a summary of the story’s moral, which I often found did not align with my own moral takeaways, but are telling about the culture out of which these stories emerged. In these Japanese fairy tales, supernatural elements like gods, demons, and goblins are invoked, although these words are subject to significant ambiguity in translation. Recall the extensive discussion about the choice of the word “genie” in Five and Twenty Tales of the Genie – this is much the same, although the translators do not say anything about their reasons for choosing to describe a given being in a particular way. I would have appreciated more insight into their thought process for such instances.

You can think of Japanese Tales from Times Past as a bit like Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. Yes, the stories which compose Konjaku Monogatarishū were first written nearly a millennium ago, unlike those in Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, which were written down from oral traditions specifically for the collection in the early twentieth century; however, the currency of the translation, and the editorial decisions of which tales to include in this particular collection, function to overlay a similarly modern fingerprint. The morals and events of some of the stories can be disconcerting to a modern reader, but they are nonetheless an immersive look at an aspect of Japanese culture from the time, coming together to paint a picture of the ways in which the natural and the supernatural were viewed, and the values of the culture which viewed them.