Histories, regardless of how they are written and by whom, are inevitably biased, but the way in which they are biased matters. If you read like I do, you might have come to the conclusion that the best histories are those which are biased towards the subject, rather like Chernow’s always-excellent biographies, which, while being honest about their subjects’ flaws and failures, nevertheless contrive to offer a generous portrait to the reader. The inevitable bias in the interpretation, presentation, and discussion of history does not mean, however, that history itself is biased – history is not an entity capable of bias, judgement, or anything else, but rather an amalgamation of human intellectual effort. How, then, can one be on the right side of history?

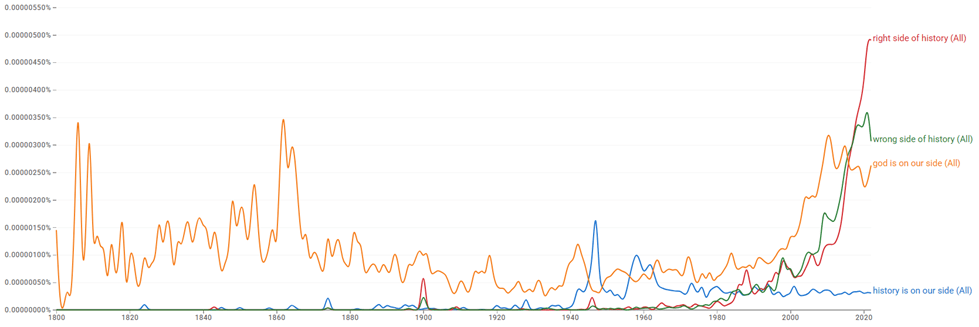

You’ve doubtless heard phrases like “right side of history” and “wrong side of history,” usually used in reference to some geopolitical actor or event as an excuse to project a kind of chronic imprimatur on the speaker’s judgement. Most of us have some intuitive sense of what is meant by a phrase like “right side of history,” the suggestion that, in the future, historians will look back at events and individuals to judge them as being right or wrong. This notion is deeply problematic for both logical and moral reasons, and its use is on the rise. Consider the figure below.

This figure was generated using Google Books’ Ngram Viewer, which analyzes the contents of 6000 English language sources from each year between 1500 and the most recent data set (which was 2022 when I generated this figure), allowing users to explore the occurrence of certain words or phrases within that dataset, in proportions to the rate of occurrence of other words or phrases. Specifically, this figure shows the per-year percentage of the selected phrases out of the whole corpus of like-length phrases. That information by itself is not particularly insightful for this discussion, but the rate of change is, and it can be inferred from this data because the sample size per year is (somewhat) controlled.

We can see, for instance, that claiming divine backing peaked in the mid-1800s, was particularly low after each of the World Wars, and has been generally on the rise again in the last two decades. Claiming history’s backing, in one way or another, remained quite uncommon until a small peak right around 1900, experienced a surge in usage during the World War II and post-war period, and began a stark ascent (the phrases “right side of history” and “wrong side of history” in particular) around 2010. A chart like this cannot begin to explore causation, but I do not think it entirely unfounded to suppose that the more-frequent invocation of history as a judgmental, justifying force corresponds with times of particular cultural foment, geopolitical tensions, and decreasing religiosity. I was rather surprised, actually, at the resurgence in the phrase “God is on our side” in the 21st century given that last countervailing trend, although linguistics like these are an imperfect reflectance of cultural reality (and also a lagging indicator in most cases).

It would be particularly interesting to look at the deployment of these sorts of phrases in 2024 and 2025, but that data is not yet available. Anecdotally, accusations of alignment with the wrong and the right sides of history became more common in the last two years, though anecdotes infamously fail to hold up in the data (another unfortunate turn of phrase to gain prominence in 2025 was “this timeline” with a plethora of crude and angsty modifiers); such anecdotal evidence prompted this post. These invocations of the right and wrong side of history seem a substitution for invoking a deity’s judgement, and they are being deployed in ways which transcend mere fallacy to become dangerously misleading.

From a logical perspective, the judgement of history supposes that a) we can know how history will judge the present, which anyone who follows the ongoing debates about our own history should realize is preposterous, and that b) future “history” will come to some kind of collective consensus with which there will be no argument, which, again, the ongoing debates about our own history should reveal to be a ridiculous notion. If we cannot even come to agreements on a judgement of events which occurred thousands of years ago, why should we expect that people ten, fifty, and hundred, or a thousand years from now would do any differently for our own time? Furthermore, when is the judgement being made? Consensus has emerged at times about events, only for that consensus to be overturned a decade later by new evidence or simply a changing of sentiment. Take Christopher Columbus’s reputational change over the past century, the numerous narratives around America’s founding, the various perceptions of the Vietnam War, or any other historical subject, and you will clearly see that if history is a judge, she is a confused, capricious one. What invocations of history’s judgement are really standing in for is the individual’s own personal, moral judgement, to which they are seeking to lend this historical imprimatur. It is really a discussion of legacy.

Morality and history, though, are distinct, and tying them together in this way is either deliberately obfuscatory or simply ignorant. Contrary to the assertions of certain branches of communist ideology, there is little reason to believe in an inevitable march of progress and history towards some destination, meaning that history will continue to evolve with the people remembering it. Legacy says more about the people doing the remembering than it does about the people or events being remembered, which is also true of things on the right or wrong side of history – such judgements say more about the people doing the judging than about what they are judging.

This is where preoccupation with history’s fickle judgements becomes a genuine hazard, for it creates a preoccupation with legacy at the expense of internal morality. It’s a kind of morality-by-tyranny-of-the-majority, wherein the right thing to do becomes that which will be applauded by the most people now and in the future. If that becomes a basis for decision-making, it will be at the expense of making decisions based on moral integrity and what is “right.” Deciding what is moral and right is no easy task, and there are no clear right answers, but abdicating the responsibility for making those decisions from the individual to a nebulous majoritarian “history” is definitely not a right answer.

Rather than seeking to lend our own moral judgements an imaginary weight by backing them with the supposed judgement of history, we should have the humility to acknowledge that we cannot know what will happen in the future or how future people will perceive our present, and the confidence to make decisions and judgements of our own based on our own morality, not based on how we imagine our legacy will be perceived by our contemporaries and successors.