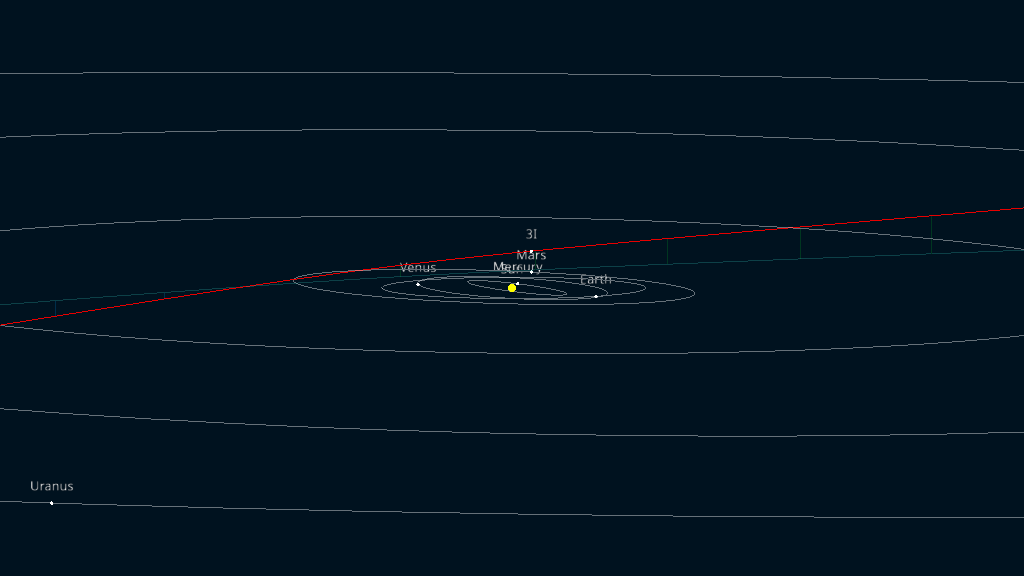

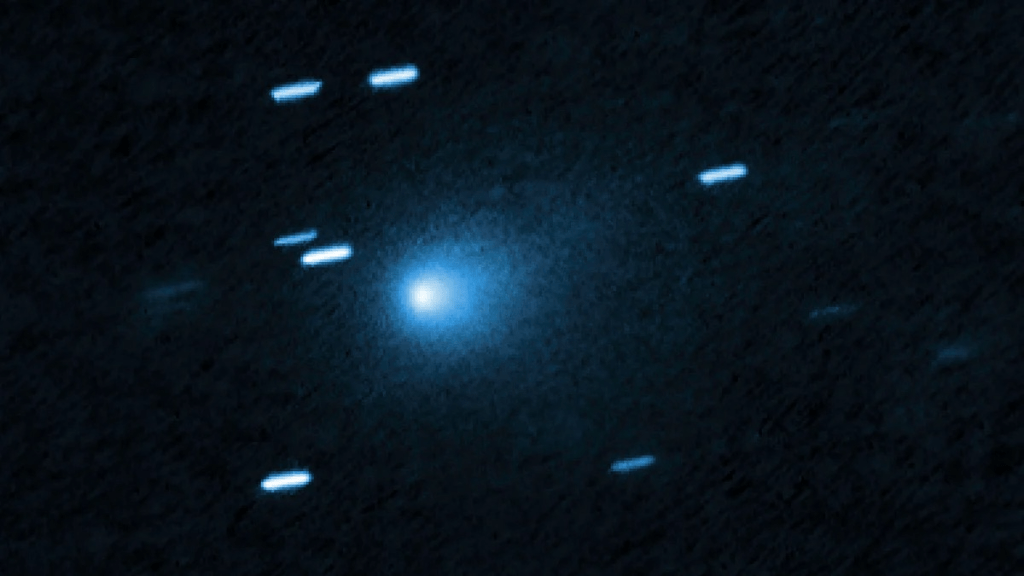

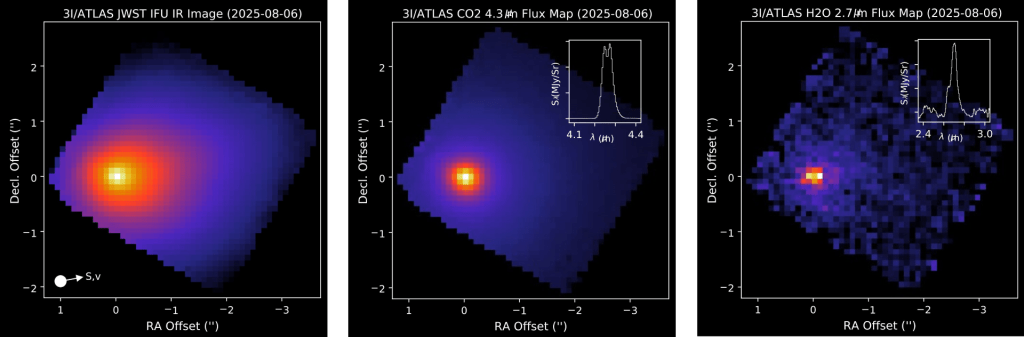

You may have heard our solar system has an interstellar visitor, comet 3I/ATLAS. This is not the first interstellar visitor we’ve identified, and there is substantial debate about just how many such interlopers there may be which pass through the solar system undetected, but this one is of particular interest because it is passing within the orbit of Mars (1.356AU), producing a relatively close approach to Earth (estimated at 2.287AU as of this writing), it is actively releasing volatiles (which is what makes it a comet, as opposed to an asteroid), and it is thought to originate from an older region of our galaxy, meaning the comet’s materials may predate the existence of our solar system by several billion years. It’s a fascinating opportunity to learn more about our galaxy’s history and the formation and evolution of other star systems, one unlikely to be repeated in our lifetimes. As such, observatories operated by NASA, ESA, and others around the world (and off it) are prepared to make as many detailed observations as possible. Indeed, a space.com article notes that several spacecraft currently operating outside of Earth’s orbit, such as those orbiting Mars, performing solar observations, or enroute to more distant destinations, may be best positioned to take observations of 3I/ATLAS from as close as 29 million kilometers.

In connection with this visitor, which is expected to make its closest approach to Earth on 19 December, and which is expected to make its closest approach to the sun on 29 October, a few folks have asked me about the possibility of launching a mission directly to the comet. After all, here is a built-in interstellar trajectory, along with the opportunity to study the object itself in far more detail. Putting aside the difficulty (impossibility?) of assembling and launching such a mission in the short timeframe in which we will have reasonable access to 3I/ATLAS, the issue is one of energy. Any spacecraft wishing to rendezvous with 3I/ATLAS will need to match its velocity, and hyperbolic interstellar trajectories are fast. I did some quick, back-of-the-envelope calculations to find just how fast.

First, let’s make some simplifying assumptions and notes about the data. I did the calculations based on a set of ephemerides for the object dating from the beginning of May. These have doubtless been made more accurate by subsequent observations, but for this purpose, it shouldn’t have much of an impact. I assumed 3I/ATLAS’s velocity could be modeled using standard orbital dynamics equations for a hyperbolic orbit undergoing Newtonian mechanics. I’m also going to be ignoring all of the real orbital geometry and timing involved in performing a rendezvous. In other words, we’re assuming that timing isn’t a factor and that the interstellar interloper’s orbital plane matches the ecliptic plane, and that our hypothetical spacecraft will be launching directly into the ecliptic plane. This is not especially realistic, but it should give us some baseline velocity numbers to play with for framing purposes.

Objects in orbit at a particular distance have a velocity based on the geometry of the orbit and the gravitational pull of the parent body. Relative to the sun, the Earth orbits at just shy of 30000 meters per second. At perihelion, 3I/ATLAS will have a velocity of almost 70000 meters per second, and it will have this velocity at a distance from the sun that, if it were in a circular orbit, would have a velocity of only 25500 meters per second. Any spacecraft attempting to rendezvous with 3I/ATLAS would therefore need to a) launch into Earth orbit; b) escape Earth orbit and enter solar orbit; c) reach the orbital distance of perihelion (a little further, realistically); and d) match 3I/ATLAS’s velocity. Again, using back-of-the-envelope calculations, this comes out to a delta-v required of about 58000 meters per second.

Now, space missions like to measure how much maneuvering capacity is required just in terms of delta-v, because it’s consistent across different thruster types and fuel varieties. If you’re not familiar with the metric, this number won’t mean much to you, but if you’re in the industry, you’ll see how enormous it is…and yet, it might not be quite as enormous as you were expecting. Certainly, I thought it would be larger. Granted, this is a low-ball estimate, not accounting for the divergence of the comet’s trajectory from the ecliptic plane or a number of other significant factors, including where the Earth will be in its orbit relative to where the comet will be for this hypothetical mission. 58000 meters per second might actually be achievable for certain launch configurations, at least at a basic glance. A fully expendable Falcon Heavy launch, for instance, may be capable of providing, on paper, this amount of delta-v for a payload mass of about 2000kg. That’s a decently sized spacecraft, larger than many of our deep space missions. However, that’s largely a one-and-done delta-v. Our hypothetical rendezvous mission would need to use about 8000m/s to reach Earth orbit, another 3,200m/s to reach solar orbit, 4,200m/s for the transfer to perihelion distance, and finally have enough fuel remaining for a final burn of a massive 42,750m/s. That last burn is the real trick, since the kinds of heavy-lift rockets capable of delivering that level of delta-v are not designed to operate in deep space for long durations, as would be required for this mission.

It’s not feasible to launch a mission to rendezvous with 3I/ATLAS and hitch a ride out into interstellar space, but I’ll admit that it’s a little closer to being feasible than I expected it to be when I decided to run these quick calculations. The timing piece might be a more significant factor for this particular visitor than the delta-v required or other, technical limitations. Conceivably, we could have a spacecraft prebuilt, waiting in storage, with SpaceX on standby to perform an expendable Falcon Heavy launch (or Starship, when it becomes operational), for the next interstellar interloper to come trespassing through our stellar neighborhood. There are a few technical hurdles to solve, of course, and we would need to give ourselves a bit more warning than we had for this one.

Speaking of warning, while we can’t go visit 3I/ATLAS, we’ll be focusing plenty of scientific instruments on it. Its peak visual magnitude from Earth is expected sometime around mid-December of this year, peaking in the 13-15 range. The faintest objects visible to the naked eye have a visual magnitude of about six, so 3I/ATLAS definitely won’t be visible to the naked eye. It’s difficult to determine exactly what the threshold for visual magnitude is when adding in various kinds of optics and sky conditions, but it’s possible – just possible – that if you happen to have a telescope in the 8-10” range that you could catch a glimpse of the comet if you manage to locate it in the night sky around the middle of December. It’s a substantial telescope, but not out of reach of a serious amateur astronomer or hobbyist. If you live near a university or college of some kind, they may have an observatory, and if they do, it probably has a telescope at least that large. I suspect it wouldn’t be hard to persuade them to take a shot at glimpsing our third-ever known interstellar visitor. Next time one comes by, maybe we’ll be prepared to go visit it up close.