You’re sitting in a car driving seventy-five down the highway. How fast are you moving? If you answered “seventy-five,” I applaud your conviction, given that I clearly set up the question to imply the obvious answer is probably not the correct one…but you’re not incorrect, either. From a certain point of view, you’re travelling at seventy-five. If you complained that I didn’t provide units, well, that’s fair, but also slightly irrelevant to today’s discussion. The units can be any unit distance per unit time – miles per hour, kilometers per minute, meters per day, lightyears per millennium – and the answer will be unaffected. The best answer, though, is that it depends (which is always a safe answer, and some of you may have gone there first). Specifically, it depends on your reference frame.

If you’ve read, understood, and internalized Relativity, you can probably skip this post, since understanding Einstein’s theories of relativity (special and general) requires a robust understanding of reference frames. The key piece of information missing from the question starting this post is a question of relativity (with a small ‘r’, not referring to Einstein’s theories). How fast are you moving relative to what? Relative to the highway, you’re moving seventy-five, but relative to the car, you’re not moving at all. Relative to an inertial reference frame with origin at the center of the Earth, your movement in the car is probably negligible compared to the velocity imparted by simply being on the surface of the rotating Earth, and, relative to the sun, the fact that you’re driving is definitely irrelevant compared to the speed at which the Earth is barreling along its orbit.

We tend to assume implicit reference frames for day-to-day matters, but dealing with space means defining and utilizing different reference frames is a routine matter. Reference frames like Earth-centered-inertial, Earth-centered Earth-fixed, heliocentric, local-vertical local-horizontal, radial in-track cross-track, body-centered, ground-fixed, polar or spherical…not to mention various custom reference frames we might develop for particular applications. There is a difference between reference frames and coordinate systems, but they are closely related, and it is worth exploring both in order to understand either. Both refer to ways of describing the dimensional environment in a precise, mathematical way.

You know coordinate systems, even if you don’t think you do. Cartesian coordinates are by far the most common, and you’ve used them without even realizing it whenever you’ve used standard graph paper. The Cartesian coordinate system is a way of dividing up dimensions into discrete, mutually orthogonal units (we will deal with only spatial dimensions for now, to keep things simple). Thus, the standard XYZ coordinate system for three-dimensional space. To locate a point in three dimensional space, you need three pieces of information, and in cartesian coordinates, those are three mutually orthogonal linear distances measured with respect to an origin, whose coordinates are (0,0,0). The choice to measure linearly and orthogonally is the choice of coordinate system, the choice of where to place the origin, the (0,0,0), is the choice of reference frame.

To fully constrain a point in three-dimensional space, you need six pieces of information: three to define its position, and three to define its velocity. That assumes you’ve already established both the coordinate system and the reference frame. You can really use any coordinate system and reference frame you want – even custom coordinate systems, which are an extremely useful concept in multivariable calculus for calculating volumes and areas of very strange shapes in arbitrary numbers of dimensions, so long as you can develop a set of parametric equations to describe the shape. A few are common, like cartesian, spherical/polar (polar is the two-dimensional version of spherical, but the term is sometimes used to refer to the three-dimensional, spherical system, too, which never gets confusing), and cylindrical.

Coordinate systems operate in the background as a way to divide up reality. Reference frames, by their nature and application, have more direct impact on what is being described. Like coordinate systems, you can describe anything in any reference frame you want, but an appropriate choice of reference frame will make things far simpler, while a poor choice of reference frame can make the situation dramatically more complicated. For instance, you could decide to tie the origin of your cartesian coordinate system to a hummingbird, and describe everything with reference to the hummingbird. The hummingbird would never move from (0,0,0), but everything around it would shift around drastically. Satellite orbits are a more practical example of this. To describe the typical orbit shape – an ellipse in some orientation around the Earth – we use an Earth-centered Inertial (ECI) reference frame, where the origin is at the center of the Earth and the reference frame does not rotate with the planet. If you tried to describe an orbit with a reference frame that is allowed to rotate with the planet’s rotation (we call this an Earth-Centered Earth-Fixed (ECEF) reference frame), the result would look horribly twisted and might not go around the planet at all. However, for describing how a satellite’s path looks from the perspective of the surface of the Earth, useful for determining ground coverage, contact times, and revisit rates, we need to use the ECEF frame.

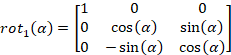

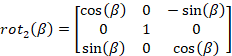

Ultimately, reference frames are all about ease of use and relevance to a given problem. It’s possible to convert between reference frames with a bit of vector and matrix math. You know, with a simple set of rotation matrices:

Where are the angles by which the defining unit vectors of the two reference frames are separated. You can convert between coordinate systems too, but that can be more a little more complicated.

The point of all this is not so you can complain to the traffic cop how the speed limit sign didn’t specify relative to what you should be going seventy-five. The point is to express the power of reference frames to change how something is understood and appears. A geosynchronous orbit depicted in the ECI reference frame appears as an ellipse around the Earth. The same orbit depicted in the ECEF frame appears as a figure eight floating in space over a fixed point on the Earth’s surface. A satellite in geostationary orbit is hurtling around the planet at some 3.07km/s (6,868mph), but to an observer on the surface of the Earth, it doesn’t appear to move. Even when you’re rushing along the highway at seventy-five miles per hour, you don’t seem to be moving that fast while you’re passing someone going seventy-four.

The concept of reference frames in the mathematical sense we’ve been using it is a powerful tool, but it need not be constrained to quantitative circumstances. Understanding how reference frames – perspectives – affect how reality appears is key to writing, too. And no, this is not a halfhearted attempt to somehow relate a mildly esoteric mathematical concept to writing so I can justify posting about it. Reference frames is another way of looking at perspective and narration. The Rhetoric of Fiction spent most of its 500+ pages exploring the different permutations of viewpoint and narration, far beyond the classic first person, third person limited, omniscient, et cetera, and another way of exploring what may be the essential decision about how to tell a story is by thinking about selecting a reference frame.

Most books, especially more modern books, even truly excellent examples like The Wheel of Time, default to the perspective of whomever is doing the thing, being the most active, the most involved. The story is presented as viewed from a reference frame whose origin is tied to that individual, and that perspective colors everything that transpires and filters what the reader learns and experiences. One of Wheel of Time’s most significant features, though, is how much time Jordan spends in tight, third person limited perspectives situated in secondary and tertiary characters, rather than the main protagonists. This gives us additional perspectives, additional reference frames, from which the view what’s happening. This is a powerful tool, which can become even more powerful if we expand the idea further.

There is a famous scene (well, famous may be a bit of a stretch) in The Lord of the Rings, where Tolkien describes the action taking place from the perspective of a fox that just happens to be wandering nearby when the main characters are going off on their adventure. Tolkien could leap between viewpoints essentially at will because he was writing in an omniscient style, although there are many permutations to what “omniscient” really means. The Rhetoric of Fiction talks extensively about the notion of a “lucid reflector,” and how the choice of a reference frame through which the story can be told that is not cohabitant with the story’s protagonist can be a powerful tool to help the story be more significant to the reader, to produce certain effects, to heighten certain ironies or clarities (or to dampen them). The Great Gatsby example comes up frequently, and I explored how different A Christmas Carol would be if told through a different reference frame. Many of the most interesting books I’ve read are ones where the story is depicted through an unexpected or unconventional reference frame. Instead of telling the hero’s journey from the hero’s perspective, what does it look like from the farmer’s wife’s? Part of what makes Hambly’s Dragonsbane such a strong novel is how it is not told from the expected perspective.

Fortunately, you don’t need to know how to do all that linear algebra I included to experiment with different viewpoints in your story. I suppose this could be considered just another post about the important of making a deliberate choice of narrator, but I think it explores a different way of thinking about how those choices affect the resulting story. It’s one thing to think about viewpoint and perspective in the abstract – it’s another to imagine, in concrete ways, how different perspectives will change the story being told. Understanding reference frames can help do that – at least, it helps me.

One thought on “Reference Frames”